There have been some big announcements in AI monetization recently:

OpenAI launched ChatGPT Pro at $200 per month for a single user, 10x the price point of ChatGPT Plus.

Sam Altman later took to X to say that OpenAI is losing money on these subscriptions — “people use it much more than we expected” — and that he “personally chose the price”.

AI startup Sierra, founded by Salesforce’s former co-CEO and already valued at $4.5 billion, announced they’re all in on outcome-based pricing.

Cognition (valued at $2B after only six months) made its AI coding agent (Devin) generally available starting at $500 per month and with “no seat limits” (there are usage credits). It promptly went viral online.

Customer support platform Help Scout “just made the most radical decision” in the company’s 14-year history (per co-founder and CEO Nick Francis) by removing seat limits. Pricing is now tied to the number of people your team helps in a month.

And those are just some highlights from the past few weeks!

Rather than seeing convergence around AI monetization, the trend seems to be the reverse: a proliferation of different flavors.

Many still sell seat-based subscriptions (see: Notion). Others are differentiating price points based on the skill-level of the AI agent (see: ChatGPT Plus vs. ChatGPT Pro). There’s classic usage-based pricing (think: usage credits at Clay) along with variants like charging for outputs of that usage (see: tasks completed at 11x) or the outcomes of those outputs (see: successful autonomous resolutions at Intercom). And then there are hybrid approaches that combine flat rate subscriptions and usage in creative ways.

Given the rapid rate of change, I’m sharing a special Sunday edition of Growth Unhinged to unpack what’s happening — and what we can learn from it. Let’s dive in.

Did this newsletter get sent to you? Hit subscribe to join the ultra exclusive club of 63,813 people who get Growth Unhinged delivered to their inbox every week.

Charging for AI “FTEs” hired

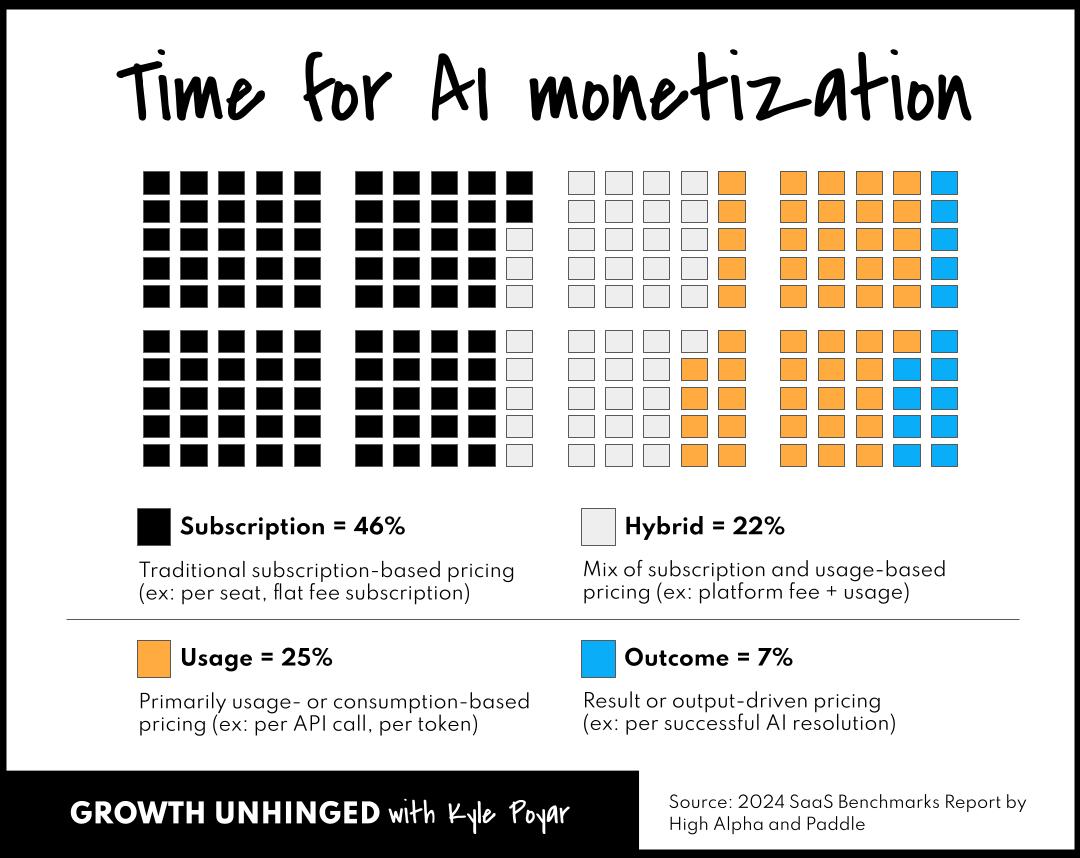

While interest in next-gen pricing models doesn’t necessarily translate into adoption, 54% of AI products are already being monetized beyond traditional seat-based subscriptions according to data from the 2024 SaaS benchmarks. This is up compared to 41% of regular SaaS products.

We’re currently seeing a mixture of usage-based pricing (25%) and hybrid pricing (22%), along with a smattering of outcome-based pricing (7%) from disruptors (see: Sierra, Chargeflow, Intercom).

As AI agent businesses continue shifting away from seat-based pricing and toward charging for units of work delivered, they tend to encounter a nagging objection from customers: your pricing is too complicated and too hard for me to predict.

One way I’ve seen folks navigate this objection: positioning as an AI “FTE” equivalent rather than a bundle of credits.

How it works:

Map the typical output or work product of a ramped human employee within a specific role (think: SDR, sales engineer, customer support rep).

For example, an SDR might research X accounts, send Y outbound emails and make Z outbound calls.

Package up this output as a SKU that your customers can buy.

Price the SKU at between 20-35% of the cost of a fully-loaded human employee after taxes, benefits, software licenses, etc.

This is roughly the approach taken by 11x, the maker of AI sales reps backed by a16z and Benchmark, as explained to me last year by founder and CEO Hasan Sukkar. 11x’s pricing is based on the number of tasks completed by the AI SDR with a task being things like identifying an account, researching the account, writing and sending a message, or scheduling a meeting when the prospect responds. 11x simplifies the buying conversation by pitching their pricing as getting the output of a top performing SDR at a cost that’s 5x cheaper compared to hiring one and that’s faster to deploy.

We’re in the very early innings of this model — few products are a 1:1 alternative for a human employee — but there are some things to like about it. Why some early adopters are digging it:

1. It taps into hiring budgets. Companies spend far more on hiring people than they do on technology. When an open role has been posted, it indicates that the budget is available. Why not go after it?

2. The value prop becomes a no-brainer — if the tech works. The customer could get the same (or better) output with a shorter hiring and ramp time, greater flexibility, no vacation days and at one-third the cost. Why shouldn’t they spin up a proof-of-concept? After all, there’s plenty of risk with hiring a human employee, too.

3. Prospecting becomes a piece of cake. The outbound email to the hiring manager essentially writes itself. Someone in your ICP posts a new req? They’re a prospect with intent. Someone has a job posting that’s been live >30 days without making a hire? They’re a prospect with intent and urgency.

4. It translates complex pricing into something that feels predictable and value-based. Buying AI credits for “tasks” completed by an AI SDR? That feels like a lot of math. Buying the equivalent output of a human SDR? That’s much easier to wrap your mind around.

It’s important to keep in mind that this model doesn’t necessarily replace a usage-based or hybrid pricing model. It’s a way to simplify your pricing for a given customer, making your product easier to buy.

From feature-based pricing to skill-based pricing

Roughly 70% of SaaS companies have some form of feature-based pricing, typically assembled into Good-Better-Best packages.

In this model, SaaS companies charge more for premium features to upsell customers from Good to Better to Best. These premium features are usually things like advanced admin privileges and role management, integrations, and single sign-on (SSO).

As I’ve said before, when in doubt, SaaS companies should default to Good-Better-Best. It makes purchase decisions fairly easy for the buyer (and for sales). It presents a clear upsell path as customers deepen their usage of the product. And it helps fund new product development by providing a path to monetizing new products.

The classic framework for building packages is to categorize features based on two axes: how many people want it versus how much people are willing to pay for it (see this explainer from the team at Simon-Kucher).

High adoption, high WTP = leader (the core of all packages)

High adoption, low WTP = filler (great candidate for upsell)

Low adoption, high WTP = bundle killer (great candidate for an add-on)

Low adoption, low WTP = try to remove from your roadmap!

I’m seeing this framework become less and less applicable for emerging AI agent products.

If we’re hiring AI to do the job, we want to un-gate access to whatever features are needed to get the job done. More access to features leads to more jobs done which leads to more money, particularly if we’re charging for units of work.

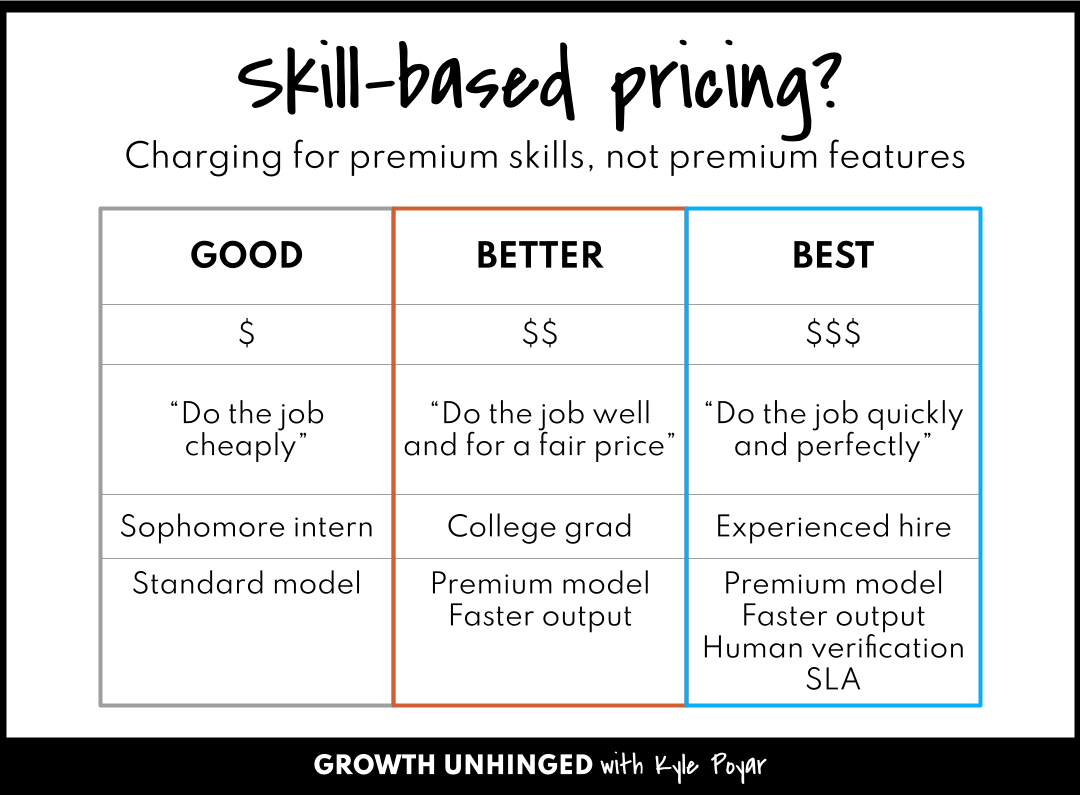

But customers are willing to pay for higher skilled work, just like they pay more to hire a PhD grad than a Sophomore intern.

In the future we could be able to charge more for things like:

Service level agreements (SLA)

Higher accuracy guarantees

Faster output or throughput of work

Better model capabilities

“Humans in the loop” to verify accuracy

If you agree with this direction, you might still want to offer multiple options for the customer. But you’ll want to orient these options as low skill (Good), medium skill (Better), high skill (Best). Think of the value proposition ladder as do the job cheaply vs. do the job well and for a fair price vs. do the job quickly and perfectly.

When #foundermode hits pricing

The most viral pricing moment of the year came early: Sam Altman took to X to say that he “personally chose the price” of ChatGPT Pro and that OpenAI is losing money on the subscription because usage levels are so high (see more in TechCrunch).

Look, I don’t want to draw too many conclusions from what’s largely a marketing ploy. But I do take it seriously because OpenAI’s pricing is THE anchor in the market — for both vendors and customers.

What’s on my mind:

1. How much of this is temporary?

If costs come down fast enough, or the product moves beyond high usage early adopters, we could see $200 per month become much more profitable.

2. Per-user pricing isn’t particularly compatible for most B2B AI products, especially as we shift from copilots to agents.

That said, in a consumer context, flat rate pricing can make a material difference to user behavior. Who remembers when AOL switched from charging an hourly fee to a flat rate of $19.95 for unlimited internet access? (This was back in 1996).

Well, the move broke the internet — in a good way. Time spent online reportedly tripled within a year of the pricing change, jumping to 23 hours per month. OpenAI’s pricing could have a similar impact.

Be careful about applying this phenomenon to a B2B context, though. Business users don’t necessarily have the same psychology; expensing a product feels less painful than putting it on your personal credit card! And business users are applying products to specific parts of a company workflow with a direct link to ROI — use cases are less discretionary compared to B2C.

3. I wish companies valued at $157B applied more rigor when making pricing decisions.

Founders are almost always the pricing decision maker — even if a company has a dedicated pricing team. But quantitative surveys, small-scale pricing tests and “what if” scenario testing can bring more objectivity to make better pricing decisions. (For more on how to run a pricing project, check out this throwback from the Growth Unhinged archives.)

It is good to see these moves. On OpenAI Pro, we only bought three subscriptions (everyone in the company gets Perplexity). We would have paid more, up to $2,000 per month, but would have started with only one subscription. There is a lot of value in o1 and a lot more value coming with 03.

Great content Kyle, tks for sharing!